06.28.2004 17:31

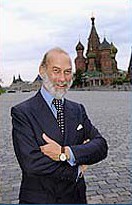

The girls in their sequinned gowns and silver-blue headdresses, singing, dancing and clapping, had eyes only for one man in the room. It was not so much Prince Michael of Kent's status as a British royal that hypnotised them; like thousands of other Russians, they were enthralled by his uncanny likeness to Nicholas II, his blood relative and the last tsar of Russia.

The girls in their sequinned gowns and silver-blue headdresses, singing, dancing and clapping, had eyes only for one man in the room. It was not so much Prince Michael of Kent's status as a British royal that hypnotised them; like thousands of other Russians, they were enthralled by his uncanny likeness to Nicholas II, his blood relative and the last tsar of Russia.

A tumultuous century seemed to melt away as a beautiful girl lassoed Michael with a floral chain and dragged him to the centre of the room amid applause.

After a couple of faltering steps, the cloak of regal formality slipped, and from under his white beard crept a smile. In time to the music of the balalaika and accordion, the prince swayed his hands from side to side. The elated girl stood on tiptoe and kissed him. Then Michael joined the throng dancing in circles beneath the ornate wooden carvings of the mansion set in a rolling Chekhovian estate.

In the Siberian countryside, where butterflies fill the air in summer temperatures, these are the theatrical shows of nostalgia for the old certainties of the royal Romanovs. In Russia's cities, too, there is a yearning for a lost heritage in these get-rich-quick post-communist times. The result is a national love affair - almost a cult worship - of Prince Michael of Kent.

No wonder the prince - whose grandfather, George V, was cousin to the executed Nicholas II - is so at home. In Britain he is at best unknown; at worst ridiculed for his wife, nicknamed 'Princess Pushy', and the playboy antics of his son, Lord Freddie Windsor. In Russia he is feted by tycoons, flown in private jets - the closest thing they have to a king.

Nearing his 62nd birthday he hurtles through at least six engagements a day, essaying countless introductions, toasts and apologies for his rusty Russian. He met endless businessmen, diplomats, arts luminaries, politicians and students. He was showered with gifts, from a Siberian factory to a vodka bottle shaped like a pistol.

At one such gathering the prince's gift in return was a brochure on Kensington Palace, where his grace-and-favour apartment taxes the patience of republicans.

Russia has many monarchists: near Red Square a beggar stretched her hands out to him with fervour. At Café Pushkin he was flanked by pretty women and took delight in teaching them the art of drinking vodka. In Siberia, people were rooted to the spot in awe at the passing of his convoy. At the opera, when an announcement proclaimed the presence of 'Prince Mikhail Kentski', there were gasps as all faces in the auditorium turned as a spotlight shone on the prince.

Such adulation, so lacking at home where he can shop unnoticed in Kensington High Street, has its downsides. He finds himself a potential terrorist target. In security circles on the trip he used the codename 'Mr White'. His police-escorted motorcade was able to flout traffic laws, he was guarded by an armed royal protection squad officer, and police marksmen lurked nearby. Michael was leading a group of British journalists to see 'the real Russia' in his capacity as patron of the Russo-British Chamber of Commerce. Day one in Moscow included audiences with two of Russia's most powerful oligarchs. Vladimir Potanin, president of Interros Holdings, and Vladimir Yevtushenkov, chairman of manufacturer Sistema, are controversial, but the prince - and we journalists - accepted their extravagant hospitality.

His entourage fiercely denies such meetings are aimed at personal profit; the only HRH not on the civil list, he makes his living from a consultancy. But in a rare interview the prince, speaking of his activities in Russia which include a new charity, told The Observer: 'I've got business interests and all sorts of things.'

Pressed, he said only: 'I'm working on that at the moment,' adding he was 'looking at' a vodka called Ivan the Terrible. 'It's apparently very good. It's very expensive.'

Meeting such entrepreneurs cannot do such ventures any harm, but those who followed Michael last week judged his a well-intentioned odyssey. The mutual love-in is real. In St Petersburg, Valentina Matvienko, Russia's first woman governor, told him: 'You are very welcome here. We appreciate your work to help friendship between our two countries.'

Later, Michael reflected on being a dead ringer for the last tsar: 'It's pure fluke. It doesn't come from Russian genes, it comes from Danish genes. I've got Danish blood and German blood and Russian blood. I've got virtually no English blood. I identify with Russians without any effort. I feel on the same wavelength.'

He added: 'I get very often asked for comments off the cuff from the press in Russia who don't seem to have any hidden agenda and to whom one can be perfectly open. But I think twice about doing that in England because I've been dealt some dirty tricks there.'

Officials at the Kremlin have joked about Michael returning in triumph one day in a tsarist restoration. 'I don't think so,' he said, noting there were numerous other candidates in the Romanov dynasty.

In St Petersburg's Hermitage museum, formerly the Winter Palace of Russia's royal family, he stopped at a portrait of Nicholas II, which made an eerie mirror. The last tsar was pictured in military battledress. 'Do you have the uniform here?' asked Michael. Possibly he wanted to try it on for size.

News source: www.guardian.co.uk

Print this news Print this news

City news archive for 28 June' 2004.

City news archive for June' 2004.

City news archive for 2004 year.

|