10.28.2005 14:39

Nikita Mikhalkov has only praise for Russian President Vladimir Putin. "No one can hold a candle to him as a leader," he says, adding that he is "worried to the depths of my soul about what will happen in 2008, the year in which Putin is going to resign. That will be a mistake on his part - the gap between him and his rivals is only getting wider. I simply cannot understand how it is possible to replace a president every four years. In the United States the only thing that gets changed is the photograph of the president's wife. The essence remains very much the same. I don't give a damn what the democrats [in Russia] think about it: It is absolutely clear to me that in Russia there has to be ruling continuity. There must be a strong central government - until when, I don't know.

Nikita Mikhalkov has only praise for Russian President Vladimir Putin. "No one can hold a candle to him as a leader," he says, adding that he is "worried to the depths of my soul about what will happen in 2008, the year in which Putin is going to resign. That will be a mistake on his part - the gap between him and his rivals is only getting wider. I simply cannot understand how it is possible to replace a president every four years. In the United States the only thing that gets changed is the photograph of the president's wife. The essence remains very much the same. I don't give a damn what the democrats [in Russia] think about it: It is absolutely clear to me that in Russia there has to be ruling continuity. There must be a strong central government - until when, I don't know.

"It is not by chance that Britain, Sweden and Denmark are not annulling the institution of the monarchy. Do you think they are all idiots there? Of course not - the people must feel that they have a father, a mother. Of course, I am not suggesting that Putin be made a tsar, but there must be ruling continuity, otherwise we will have a catastrophe. Ruling continuity, armed evolution and enlightened conservatism - and if the president is expected to be accountable for everything, he must be given ruling power."

Power, for Mikhalkov, is closely related to the earth. "I don't know the first thing about Israeli politics," he says, but immediately adds that he has no doubt that only a strong individual with roots in the soil, like Ariel Sharon, could lead the disengagement move.

And what is armed evolution?

"Russia must undergo what I call `armed evolution,'" he reiterates, offering an instant solution to Russia's international status. "Not revolution, but evolution."

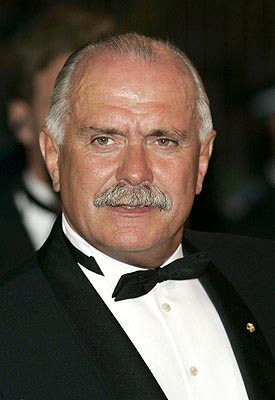

It is not only in the cinema but in real life as well that Nikita Sergevich Mikhalkov likes to play the mysterious Russian soul. He was in Israel last week as the guest of the Russian Film Festival mounted by the Tel Aviv Cinematheque, and the conversation with him took place in Russian in a hotel in the city. Tall and robust with an almost unlined face despite his 60 years, he sports a terrifying mustache. His eyes glitter when he talks about the only author he is reluctant to bring to the screen - Dostoevsky. "He is the only Russian author about whom it can be said that he is a true St. Petersburg man. After all, everyone wrote there, drank there, lived there for certain periods in their lives. But he is the only one who was a son of St. Petersburg to the depths of his soul. On the surface everything is clear in his work, simple, and it looks as though it would be possible to start acting and shooting immediately. But the moment you begin to dig, you are immersed in the depths of the abyss."

Classical Russian literature is at the center of Mikhalkov's work. For many, his adaptations of Chekhov's "An Unfinished Piece for Player Piano" (1976), and more especially, of "Dark Eyes" (1987), which was shot in Italy and starred Marcello Mastroianni, are models of the cinematic interpretation of literature. Ostensibly minor "Chekhovian" characters, reticent and touching, accompany Mikhalkov in many of his other films as well. Foreign literature is of less interest to him. "I do not like tourists," he says, "and to adapt for the screen a work that belongs to a country I don't live in is like being a tourist."

Still, after Dostoevsky, Mikhalkov recalls a completely different writer. "I received the rights to film `The Alchemist' from Paulo Coelho, the book's author. If, God willing, I make the film," he says in all seriousness, "I will move the plot to Chechnya, to the Caucasus."

The Russian equivalents of "God willing" or "with God's help" recur frequently in the interview: Mikhalkov is a devout Russian Orthodox Christian, who takes pride in being one of those who led the recent move to organize a reburial in Moscow for General Anton Denikin, who fought with the White Russians against the forces of the Communist revolution - though many regard Denikin as a bloodthirsty madman who, among other atrocities, carried out pogroms against Jews. "Before we brought Denikin for burial, I visited a church in Paris and I suddenly understood what the lot was of these people who fled from the Bolsheviks. They could go anywhere they wanted in the world - New York, Los Angeles, Madrid - but the most important thing was denied them: to return home."

Mikhalkov would also like to remove the mummified Lenin from the mausoleum in Moscow and inter him in St. Petersburg. Explaining his support for this proposal, he told the Russian press, "Many people admired Lenin and many hated him, but how much do you have to hate someone in order to go on abusing his body after 80 years? Lenin, after all, was baptized when he was born, and his last wish was to be buried next to his mother."

Of this idea - to remove the most mythological vestige of the Communism that Mikhalkov abhors - an anonymous wag wrote on a Russian Internet site, "Mikhalkov wants to take Lenin out of the mausoleum in order to make room for himself."

People are afraid of us

Mikhalkov was born a few months after the end of World War II to a family with ramified aristocratic roots, and straight into the arts. His grandparents were painters, his mother was a poet. His older brother is the film director Andrei Konchalovsky, who lives in the United States. His father, Sergei Mikhalkov, was a children's writer and the author of the lyrics to the Russian national anthem in its two versions (the second version omitted Stalin's name) and to the new anthem as well (the melody was unchanged). This biographical detail is only one of an array of contradictory elements that make up the very colorful mosaic of Nikita Mikhalkov, considered Russia's greatest living film director; he is chairman of the Russian Cultural Foundation, chairman of the Russian Cinema Council and holds various other honorary positions.

Sometimes it seems that a true gulf exists between this creative artist, who made the marvelously humanist film "Oblomov" (based on the classic novel by Ivan Goncharov), about an aristocrat who idles his life away sleeping and lounging on a sofa, and Mikhalkov's views about society and politics. Indeed, it is hard to refrain from saying of the hyperactive Mikhalkov that he is the opposite of the somnolent Oblomov. Even before the major international success of his "Burnt by the Sun," which won the Oscar for best foreign film in 1994, Mikhalkov plunged into the bizarre depths of domestic politics in Russia. He does not for a moment hide his nationalist outlook. In 1995 he was elected to the Duma, the Russian parliament, on behalf of a party whose name is very reminiscent of an ultranationalist Israeli party - "Our Home - Russia."

Of Boris Yeltsin, his country's former president, he has only two good things to say. The first is that Yeltsin, when all is said and done, displayed courage when he returned his Communist Party membership card in a period when it was still impossible to foresee clearly the collapse of the government. The second is that he resigned as president of Russia. Rumor had it that Mikhalkov himself, after playing the role of the tsar in his last film, "The Barber of Siberia" (1999), was preparing the ground for a campaign of his own to be elected president. However, that was before Putin came to power.

What is the source of the difference between Putin's image in Russia and outside the country?

"People are simply afraid of us. Alexander III once said to his son Nikolai, the last tsar of Russia: Russia has no allies apart from its army and its navy. The West is afraid of our strength. It is a very serious and a very ancient fear. When there were two poles, two superpowers - and it makes no difference now which was good and which was bad - there was at least a clear balance. It was clear to everyone in the world what the options were. I, for example, am 100-percent convinced that what happened just now in the United States - the hurricane that destroyed New Orleans - was not accidental. It is a salient result of the lack of balance. After all, how is it possible that this tremendous superpower, with all its technology, is impotent in the face of some tornado?"

Can disasters that occurred in the Soviet Union also be attributed to divine power? Do you think, for example, that the Chernobyl disaster was a punishment from heaven, a punishment intended to arouse the nation?

"Of course. How is it possible not to punish a people that betrayed everything it held sacred for a thousand years? And we are still paying for that. Democracy always existed in Russia - in the church. Everyone is equal before the altar - the poor and the tsars. What happened outside the church is a different story. When the Bolsheviks uprooted that, they did not give us anything in its place. Russians do not like to obey laws that were enacted by other people. In fact, they do not like laws at all, only laws that come from above. The Bolsheviks, of course, fully exploited the genetic memory of the people. No tsar was praised like Stalin, you know."

That light, that summer

Mikhalkov began to act in films at the age of 14. He became famous at the age of 18, when he starred in the cult film "I Walk in Moscow" (1963). He then studied film, one of his teachers being the legendary director Andrei Tarkovsky. He started to direct films in the 1970s and won immediate acceptance in the Soviet Union and abroad. The gentle light of dusk, summer and the village, the nostalgic and longing gaze at childhood and the past are major elements in his work.

"Cinema is always cinema but also something extra," he says. "That light, that summer - that is apparently the extra element I bring." When I compare his use of color and composition to paintings by Renoir, he agrees half-heartedly, but immediately notes that he is close to a number of Russian painters, who are not very well known outside his country: Surikov (Mikhalkov's great-grandfather), Leviatan, Soroka, Venetsianov and others.

One of Mikhalkov's first films, "A Slave of Love" (1976), is about an attempt to shoot a silent film in the period of the Communist revolution. It is a very self- conscious melodrama, but still, despite its subversive nature, pro-Soviet, as was required then. In one of the film's moving scenes, the director of the silent film says, "In my childhood, when I was afraid of something, I would close my eyes. And now," he adds, turning to the crew, "now let us go outside, into the fresh air, and not open our eyes." Mikhalkov's father's ties to the Soviet government always generated suspicions that Mikhalkov was given far more freedom than other creative artists of the time.

Did the Soviet censors cause you difficulties?

"All the time. For example, I received 116 demands for corrections in my film `Family Relations' (1982). But I never had a problem bypassing and tricking the censors. Essentially, I am not a dissident. I have no interest in an all-or-nothing approach. But I am certainly not a coward, either. I would fragment one correction into ten, change something here and immediately put it back somewhere else, preserving what was truly important to me. You don't want me to make this film? That's fine - I will make a different film. But a film that consists of my material, not theirs. And if they were insistent about the corrections, I would tell them, Fine, no problem, but I want my name removed from the film, because that's the only thing I have, you know - my name. That already frightened them. The censors pressured me no less than others, but it never interested me to talk about it. In the end, I did not direct anything I did not want to direct."

I am a patriot

Mikhalkov is now filming a sequel to "Burnt by the Sun" in Siberia. Sergei Kotov (played by Mikhalkov), the colonel who was betrayed by Stalin and sent to prison or death at the end of the first film, escapes from the Gulag, which is bombed at the beginning of World War II, and finds himself at the front as a simple soldier.

Why did you want to make a film about World War II?

"Chekhov wrote, `Behind the door of every happy, contented man stands someone with a hammer continually reminding him with a tap that there are unhappy people.' We are constantly forgetting how close everything is to us: life and death, sickness and health, love, everything. In an instant a person can become someone else. This film, with God's help, I will make in such a way that everyone who sees it and comes out of the cinema and gets into his car, say, will think, `What happiness that I can now get into my car, or the subway, or read a newspaper. How fortunate that I am alive, that I am not in a war.'"

What do you think of the way World War II is presented in Western cinema? Did you like `Saving Private Ryan'?

"Technically, that is an extraordinary film. But children can be conceived either in bed or by test-tube insemination. A nation that never waged a war for its territory cannot make a true war film. And in any case, a war that takes place on the ground is something else entirely, not just a matter of missiles that whistle by somewhere. In the Soviet Union, too, you know, hundreds of films were made about World War II, by hundreds of very different directors. But in fact all those films had one director: the regime. There was always some taboo that could not be broken.

"Incidentally, I was not able to accept that in the textbooks that George Soros provided to Russia, the Battle of Stalingrad gets four lines, while the invasion of Normandy gets five pages. Like it or not, the war was won by the Soviet Union. Not that it's all black and white - there was the Ribbentrop-Molotov pact, there was the partitioning of Poland. Nevertheless, and I am not alone in thinking this, the Russian soldier was deprived of the victory in World War II by the Soviet historians. They portrayed the Germans as idiots. But that was a tremendous army, the German army! Countries fell to the Wehrmacht in five days. Did you know that their uniform was designed by Hugo Boss? Really. They were an incredibly powerful army, and the fact that we defeated them ... and not five idiots somewhere with crooked bandages on their foreheads ..."

Despite his anger at the false representation of the war in films, Mikhalkov does not think that art should educate. "Fellini has a wonderful response to this in his film `8 1/2,' when Guido Anselmi, played by Mastroianni, says, `I want to speak the truth, the truth that I do not know but that I am looking for.'"

To illustrate the elusiveness of truth, Mikhalkov suddenly launches into a story about how he and two friends entered what they thought was a night club in Moscow but turned out to be a kind of bordello. "We were stunned, but we decided to stay anyway. We went upstairs, ate and drank beer. A beautiful girl came over to me and asked for my autograph. I asked her what her name was. `Natasha,' she said. I asked how old she was. Seventeen, she said. I asked where she was from. From Sartov, she said [a city on the Volga River]. After I wrote a dedication, `To sweet Natasha,' or something like that, she said, `Nikita Sergevich, I grew up on your movies, you know!'"

"I am a patriot," Mikhalkov declared during the interview, and added that in his films he does not seek to present solid answers but to ask the right question and hope that this will generate answers for those who are looking for them. While he replied to my questions, both the right ones and the wrong ones, I could not help recalling that the Canadian writer Margaret Atwood said that to want to meet a creative artist because you like his work, is like wanting to meet a goose because you like foie gras.

I thought that perhaps, after all, I should end the interview by asking a question about the cinema; that maybe it would be good if the end, unlike much of what he had said, would be less pointed. I asked Mikhalkov who his favorite directors are, which director can bring him to tears. He replied immediately, "Milos Forman." Then he lapsed into thought for a time, which for a moment seemed too long, as though he had suddenly run out of words. In the meantime, I recalled at least three Mikhalkov films that had brought tears to my eyes: "Burnt by the Sun," "Urga" (1990) and "Oblomov." Then he started to talk about Fellini, about Bergman, about Kurosawa, about Jean-Pierre Melville, about Kusturica and others. Finally, he again noted the director he loves most of all - Forman.

Thus there remained unresolved the disparity between the public person Nikita Sergevich Mikhalkov and the filmmaker Nikita Sergevich Mikhalkov. And I was unable to answer to myself which of two roles in Forman films would suit him better: a supporting role in "One Flew over the Cuckoo's Nest," or the lead in "Amadeus." n

News source: haaretz.com

Print this news Print this news

City news archive for 28 October' 2005.

City news archive for October' 2005.

City news archive for 2005 year.

|