10.28.2005 14:13

What would you do with Ksenia Sobchak’s organs? The new satirical magazine Krokodil has a suggestion for the bits of the It Girl of today.

What would you do with Ksenia Sobchak’s organs? The new satirical magazine Krokodil has a suggestion for the bits of the It Girl of today.

First comes praise: Sobchak fulfills an important state function, one of the first articles in the magazine asserts, calling her “the bearer of the nation’s genetic code, the symbol of its dreams, the real image of the flowering and brains of the riches of Russia.”

Then the solution: “When troubles fall on the motherland, Ksenia Sobchak’s organs can be sold off, which will undoubtedly preserve the beauty of the Russian person in the world and help ease the nation’s terrible economic problems.” The praise then continues discussing the It Girl’s finer parts, from her pink little ears to her little pink brain.

Sobchak, the wealthy socialite host of the “Dom-2” reality show, is a symbol of all the things that editor Sergei Mostovshchikov hates about today’s society. His new magazine is a revival of an old Soviet satirical journal that probably would have hated Sobchak too.

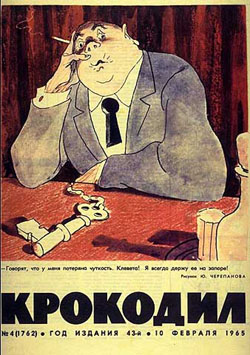

The original Krokodil, or Crocodile, was founded in 1922, a few years after the Revolution. It was a time when dozens of satirical publications bloomed milling for an eager audience. But the majority were shut down as censorship took root, with only Krokodil surviving into later years.

It was a satirical magazine but its ultimate aim was to support Soviet society. Its cartoons and articles attacked what the government considered social ills. That didn’t mean its satire was toothless. Soviet cartoonists attacked familiar topics: the gabbing of committees, the pompousness of local leaders, the groveling before officials and even bribery and corruption. Many of the country’s foremost writers — including Vladimir Mayakovsky and Sergei Dovlatov — contributed to Krokodil at one time or another.

This month, Krokodil was revived after a lingering death in post-Soviet times. Based in Moscow, its office

is down the corridor from the office

of Novaya Gazeta, the biweekly paper that has opposition, if not satire, running through its veins. The building, which belongs to Moskovskaya Pravda printers, is one of those old Soviet buildings with long, dusty corridors and signs on the walls with cartoons on how best to put out a fire. The door to the Krokodil office, a small room for the four full-time Staff Writers, is covered in a green, scaly piece of what looks like crocodile-skin wallpaper.

During a recent interview in the office, Mostovshchikov defined the new Krokodil in terms of what it stands against.

“It is anti-society and against the morals of today’s society,” he said between cigarette puffs.

The editor listed face control, glossy magazines and Chechnya’s controversial deputy prime minister as some of the new ills facing Russian society. “If a person doubts that Ramzan Kadyrov is a Hero of Russia, then he is our reader,” he said.

Also on the editor’s hit list is the ubiquitous (some would say obnoxious) television host Vladimir Solovyov. “That’s the kind of guy who you would never let into your house,” Mostovshchikov said.

In look and feel, the magazine is different from any other. Despite having the same price as a glossy, a hefty 149 rubles, it comes wrapped in a brown paper envelope reminiscent of an old Soviet post envelope — or a wino’s drink bag. It is printed on old Soviet-style paper that took the publishers ages to find, Mostovshchikov said.

“We searched for months,” he recalled. They eventually found it in a town in the Vologda region where it was being used to make school books. The first issue of the magazine has only one ad and that, for a tourist company offering vacations in the Carpathia region of western Ukraine, could be taken for a joke.

Across the envelope of the first issue is the large headline “There are two days of oil left. Page 9.” Inside is a 48-page magazine whose cover features a bear with very sharp teeth dancing with a hunter — the magazine with its audience — and a few bay leaves thrown in as a present.

The issue, with a limited run of 20,000 and initially limited to sale in Pyatyorochka supermarkets and BP gas stations in Moscow, has been swept off the shelves thanks to its sharp humor, cartoons and undisguised contempt for some of the favorite bugbears of modern Russia.

Mostovshchikov wants to satirize the things that no one else satirizes. And there are surely no other publications that would publish a cartoon of Chechen warlord Shamil Basayev with a bomb on his back, bumbling along in a pastiche of the Soviet version of Winnie the Pooh.

One whole page of cartoons has the title “How the Ukrainians are Dangerous.” It begins in the first frame with a devilish scene of eggs hatching on a bleak hillside, and claws or perhaps tails poking through the shells. The caption underneath says, “There are 50 million of them.”

Another picture shows Darth Vader walking into a room full of provincial 19th-century Russians. The caption reads, “Moscow proposes to return certain powers to the regions.”

One whole page is taken up with a cartoon called “Catastrophes of the 21st Century” that shows an aerial view of Triumf-Palas, a recently-built and much-derided neo-Stalinist apartment block. The building is cracked and crumbling, with smoke pouring into the sky. Bombing it from above are two angry, airborne squirrels. The subtitle is “Attack of the Park Squirrels on Triumf-Palas.” It’s a surreal, almost New Yorker-ish picture, although rooted in reality — Triumf-Palas was built on the site of a park famed for its squirrels.

The playfulness represents traits that Mostovshchikov has taken from magazine to magazine.

Mostovshchikov’s biggest success was his first editorship at Stolitsa, a wickedly funny satirical journal that appeared in 1996 and had burned out by the end of the following year. It issued bumper stickers with pictures of Zurab Tsereteli’s Peter the Great statue and had a nihilist, often evil sense of humor. He went on to edit Bolshoi Gorod, Men’s Health and Novy Ochevidets, none of them for very long. The last was an attempt to bring The New Yorker, in style and content, to Russia — it even replicated the look of the venerable U.S. weekly down to its cartoons, layout and choice of fonts.

The editor said he was aiming to turn Krokodil into something like The New Yorker.

But for the English-speaking reader, it may be more reminiscent of the eXile, the scandalous alternative English-language newspaper.

Parts of Krokodil echo the eXile’s risk-taking and — for some, maybe — its offensiveness. That being said, however, there is about as much material in one issue of Krokodil as in a year’s worth of eXile.

“The eXile is a great publication,” Mostovshchikov said, adding that it is in opposition to The Moscow Times (sister English-language newspaper of The St. Petersburg Times), with one publication representing one thing, the other its complete opposite. In Russian publishing, he said, there is no such opposition.

One critic has said, and not as a compliment, that all of Mostovshchikov’s magazines have been versions of Krokodil, but only now has he finally managed to get the brand name to match the content.

Despite his neighbors down the corridor, the editor denied that he was setting up a political paper. Rather, he said, his target was society as a whole.

One of the problems he has faced was a lack of both satirical writers and cartoonists, he said.

Indeed, the quality of the first issue varies widely, often turning verbose in the text or obscure in the cartoons. At its best, though, there is something you cannot find in any other Russian publication.

On the back of the issue is a drawing of a scene from an Indian film, with the word Krokodil written in fake Hindi script.

Underneath is a preview of what may come in future issues: “The cats close down the Kuklachyov Theater, the Bee Gees in the Kremlin, a complete timetable of all hurricanes and suburban trains, the first Russified chessboard and Bruce Willis against sausages and green peas.”

News source: times.spb.ru

Print this news Print this news

Culture news archive for 28 October' 2005.

Culture news archive for October' 2005.

Culture news archive for 2005 year.

|