11.02.2005 16:03

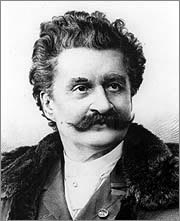

Johann Strauss, Jr., the “Waltz King,” spent 11 summers in the mid-1800s entertaining St. Petersburg high society at Pavlovsk’s musical train station. The 180th anniversery of the composer’s birth on Oct. 25 1825 was marked on Tuesday.

Johann Strauss, Jr., the “Waltz King,” spent 11 summers in the mid-1800s entertaining St. Petersburg high society at Pavlovsk’s musical train station. The 180th anniversery of the composer’s birth on Oct. 25 1825 was marked on Tuesday.

In the new Vitebsky railway station in southern St. Petersburg, smartly dressed men and women rush about to catch their trains. The women look elegant in their fabulous evening gowns, which are puffed up and back-weighted in the latest 1850s fashion. Excitement is running high and everyone is preparing themselves for the short train ride to a grand evening of world-class music and dancing.

The Waltz King is in town.

Johann Strauss, Jr. arrived in St. Petersburg at the start of an exciting new era in Russia. It was 1856 and the new tsar, Alexander II, had just announced the end of the Crimean War and promised new economic reforms and modern advances, including expansion of the nation’s railway lines.

On Oct. 10 1837, Russia’s first railway was inuagurated, running from St. Petersburg to Pavlovsk, a royal palace. The train station at Pavlovsk was nothing less than royal Russian extravagence, recalling London’s Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens — giving rise to the Russian word vokzal — a train station.

The magnificent terminus was called “The Musical Station” and was surrounded by a beautifully manicured park and included among its many amenities a concert hall to seat one hundred.

Some years after its construction, the Russian railway company invited Strauss Jr. — the scion of an Austrian dynasty of composers — to play at the station. He arrived with a 26-man orchestra and played his first concert on May 6, 1856. And so began St. Petersburg’s 11 seasons of Strauss.

Strauss was instantly popular in Russia, especially among the ladies. Portraits of their idol were widely sold in bookstores, and jewelry shop windows carried rings and brooches with his image. Even uptown florists offered bouquets named after his waltzes. Strauss was, in short, the 19th century equivalent of a pop star.

Love in St. Petersburg

One particular St. Petersburg lady was very taken with Strauss — and the feeling was mutual.

Olga Smirnitskaya, the daughter of a Russian bureaucrat, was a sensitive person with a talent for the piano and a composer of several romances. After she met Strauss in 1858, the young lovers employed adolescent strategies to keep their relationship a secret. They wrote notes to each other on candy wrappers and delivered them through mutual friends. Later, they would play hide and seek in a particular tree trunk in the park at Pavlovsk. The nearly a hundred letters written between them that exist today are wonderfully romantic.

Strauss’ compositions “Viennese Bonbons” and the remorseful “Parting with St. Petersburg” were inspired by Smirnitskaya and the love they shared.

Sadly, women of that era did not marry outside their social rank, even to composers as great as Strauss, and in 1860 the affair ended when her parents refused to sanction a union.

Despite this, Strauss was admitted to the highest levels of St. Petersburg society and was considered a friend of the Romanovs.

The Royal Family

Tsar Nicolas I’s youngest son, Mikhail, himself a skilled musician, became very close to Strauss through their mutual passion for music. Tsrevich Mikhail even displayed his talent publicly, occasionally playing violin in Strauss’ orchestra at Pavlovsk. Several of Strauss’ compositions were written for or influenced by the Tsar and his family.

For esample, Opus No. 107 was written for the occasion of Tsar Nicolas’ and his sons’ visit to Vienna in 1852. The piece is filled with good humor and was praised by the press for being a breath of fresh air from the normal pomp and circumstance that other composers were churning out for such occasions.

“The Coronation March” was the first of Strauss’ works to be played in Russia, written in honor of Tsar Nicolas II’s ascension to the throne and his September 1856 coronation.

But honoring the leaders of Russia was not always a politically wise decision.

Strauss’ homage to Tsar Alexander II, presented in 1864, came after a high-profile and unpopular massacre of nationalist revolutionaries in Poland. In Strauss’ hometown of Vienna, the homage would have outraged high society as a tribute to a monster, or worse, a tribute to the massacre itself. The piece was actually written for a concert benefiting Polish orphans and widows, but Strauss was still afraid of political backlash so the work was neither published or played in Vienna.

“Public Relations” often played a significant role in Strauss’ management decisions. The titles of several of the works he wrote for Russian audiences were changed when they were published in Austria to reflect Viennese tastes and attitudes.

Discovery of Tchaikovsky

Strauss could also be credited for bringing Pyotr Tchaikovsky to the world stage. While still in school as one of the first students of the St. Petersburg Conservatory, the young Tchaikovsky became a favorite of Professor Anton Rubinshtein.

It was Rubinshtein who brought Tchaikovsky’s school project “Characteristic Dances” to Strauss’ attention. Strauss quickly recognized the budding genius in the piece and gave Tchaikovsky his first concert.

The envy of all his schoolmates, Tchaikovsky, who as a young boy was considered a worthless music student, conducted to the crowd’s delight.

From that moment forward, Tchaikovsky was destined to become one of the world’s most loved composers. Strauss’ 11 magical summers at Pavlovsk were ended with the composition “Russian March Fantasia.”

He was to have performed the piece during his 12th season in Russia but St. Petersburg’s fans never heard it. Strauss skipped out on the Russian capital and instead accepted an invitation from the “World Peace Jubilee” in the United States.

Strauss did not, however, consider the legal consequences of his change of plans, which ended up costing him dearly.

The Russian railroad authorities sued him in court for breech of contract. Though Strauss came back to Russia in 1869, 1872 and 1886, Strauss would never again play at Pavlovsk.

Fall and Rise

The Russian composer Mikhail Glinka took over the reins from Strauss and the Musical Station lived on until 1917, when, like so many things in Russia, the music stopped.

During Soviet times, Strauss was still popular but slowly lost influence as his genre of music died out.

In 1999, however, a year declared by the Austrian goverment as the Year of Johann Strauss, the Musical Olympus foundation hosted a revival in St. Petersburg called “Remembering Johann Strauss.”

“The economic situation at the time was difficult,” said Executive Secretary Marina Balakina, “but we felt that despite the difficulties of everyday life, people should recall old traditions like this one.”

The balls were held for only four years but were replaced by the annual Grand Waltz Festival which this year celebrated Johann Strauss’ 180th birthday (see box).

This interest in Strauss’ music in St. Petersburg is itself a sign of the great influence the Austrain composer had on the cultural and musical life of Russia.

Those 11 musical seasons facilitated a sentimental and cultural link between Vienna and St. Petersburg at a time when Russia was searching for European influence.

News source: sptimes.ru

Print this news Print this news

Culture news archive for 02 November' 2005.

Culture news archive for November' 2005.

Culture news archive for 2005 year.

|